The call for THATCamp reflections in the wake of the project’s sunsetting has generated a lot of interesting writing, as well as an informal record of some of the networks that intersected with (and, in some cases, emerged from) this “unconference” initiative (if you are unfamiliar with THATCamps and are still reading these words, here is a general overview). I wanted to get some thoughts in writing here on my experiences with THATCamp and the value of the unconference model in public humanities and academic contexts.

My first THATCamp was one officially sponsored by the Modern Language Association in January 2013 (there was also a “Digital Pedagogy Unconference” that year at MLA; that’s a lot of unconferencing tbh). I went because it was hosted by Northeastern, where I was a doctoral student in English. DH was increasingly on our radar in English thanks to Elizabeth Maddock Dillon’s encouragement and to the recent arrival of Ryan Cordell, among other factors. In addition to attending, many graduate students were part of the labor involved in setting tables up and organizing session Post-It Notes and things like that.

I pitched a session on “Archiving the Archivists of the Twenty-First Century” that was inspired by my developing interests in born-digital poetry, the remediation of poetry in digital spaces, and the networks of poets, readers, critics, and scholars materializing on social media and around blogs (I ended up talking a bit about this stuff in my dissertation). I hadn’t worked a lot in physical archives or collaborated with archivists and librarians, which is why I was writing things like “Are we in an Age of The Archivist?” and “Why not allow an archive to interact more with the rest of the web?” like I was the first person to write such things (I still think that second question is a good one; nice to see Smithsonian Open Access launch this week, in related news).

My pitch got accepted and added to the morning schedule, where I was joined by a small crew of folks who had been doing and thinking about this sort of work for a while, including Matthew Battles, author of Library: An Unquiet History (which is sitting here on my personal library shelf in my office). And they were all super nice and encouraging and convivial and extremely patient with a doctoral student extremely new to this world. We talked about the use and over-use of the term “archive,” the roles classrooms and institutions play in shaping archival encounters, and interesting digital projects and tools, among other topics.

Re-reading my lengthy session notes, I can see how excited I was to be hearing and learning about these sorts of things. I’m not sure what my extremely-knowledgeable peers got from the conversation, but the session no doubt informed my decision to apply for a job on the Our Marathon digital archive project a few months later. And I started writing this post from my office at Brown, a place I never thought I’d be allowed to visit, let along work at, and I’m taking a break from a semester where I’m teaching two courses that work explicitly with archives and digital contexts (here’s the public-facing course site for one of them).

That’s a relatively neat and tidy narrative full of positive vibes up there, isn’t it? While I want to acknowledge the role THATCamp played in my own career trajectory, I also want to trouble the takeaways from a trajectory that too neatly inscribes cause and effect.

THATCamps and The Institutionalization of DH

Dan Cohen talked a bit about the non-hierarchical dimensions of his THATCamp experiences, and the memories of fun times at THATCamps. I don’t know if I’d say that my THATCamp experiences have been non-hierarchical or fun. I will say that, at the 2013 session I just described and at the event at-large, folks were extremely generous and seemed less concerned with hierarchies when it came to respecting other people’s points of view and sharing advice and resources. But I think it’s easier to set aside those hierarchies for a few hours when you’re occupying a particularly comfortable perch in a profession, or when you’re heading back to an institution that provides you with resources and networks to act on what was learned at a THATCamp. So it seems important to acknowledge where THATCampers go after the day has ended and how these professional contexts might shape what seems fun about them.

The first THATCamp was in 2008, a year more commonly commemorated as the arrival of The Great Recession. By 2013, digital humanities already had some pretty dominant cliques, institutional contexts, methodologies, and terminologies. And THATCamp’s affiliations with DH transformed some of them into spaces where the tensions, anxieties, and professional realities of the academic sub-field were readily apparent. MLA can already be a pretty tense place for attendees navigating the job market, and regional THATCamps hosted by particular institutions can yield a range of attendees but also remind folks of the hierarchies and power dynamics of a regional DH scene like Boston. I had and continue to have pretty strong professional ties with folks from a range of institutions in the New England area, but I acknowledge that my time at Northeastern and now at Brown has likely shaped those interactions in implicit and explicit ways.

In 2013, I was fortunate to be at an institution that needed graduate students to help them think through its relatively-new investments in digital humanities, one that was developing projects that required our input as well as our labor. I’ve been at other THATCamps where there was at times a clear disconnect between the recommendations and approaches described by their more vocal participants and the institutional and professional realities of attendees looking to get started or constrained by an absence of local collaborators, institutional resources, or job security. And I’ve been at THATCamps where administrators and senior scholars in attendance would, intentionally or unintentionally, come across as a bit extractive, asking junior scholars for recommendations but offering little to nothing in exchange. I’ve even seen some incidents of “THATCampsplaining” when a particular organizer has deviated in some well-intended way from the platonic THATCamp model. That’s not so fun.

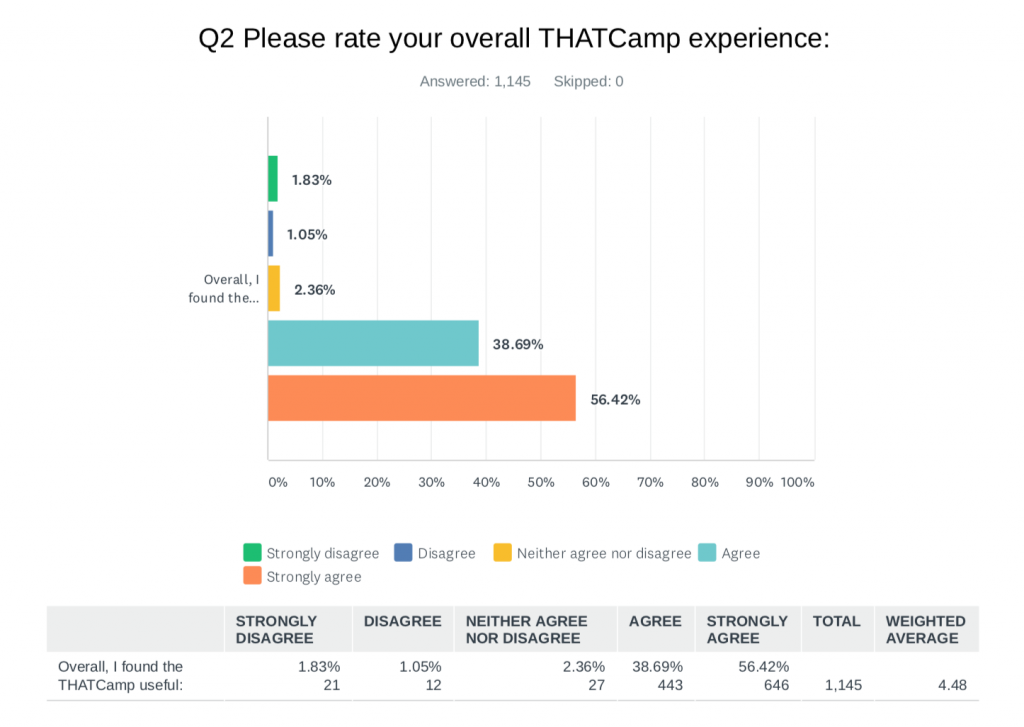

In any case, one interesting complement to the blog reflections (which is likely underway) might be a data-oriented analysis of THATCamp attendees and their networks: where they were then professionally, where they are now, how these sessions fit into digital humanities trajectories, what percentages of folks began or continued doing work legible as DH, how this pool of THATCamp participants and organizers fits into the state of digital humanities in national and global contexts in 2020, what was happening beyond THATCamps between 2008 and now. I know that the story of the institutionalization of DH is an ongoing one that also precedes this time frame, but this period seems like a particularly compelling block of time to survey and analyze.

Moving Beyond the Conference / Unconference Binary (yes, this is about public humanities)

An “unconference” is legible to participants and attendees who have been to academic conferences. It can be more difficult to explain an unconference model when you’re developing programming for wider audiences. Why would you bring the unconference model into these contexts?

At Brown’s Center for Public Humanities, we have found the unconference to be an interesting foundational model for our annual Hacking Heritage event. But as the program enters its fifth year in an annual format, we’ve been reflecting on the limits of the unconference as implemented by THATCamp and similar initiatives like Bmore Historic (the latter of which was the catalyst for our own unconferencing).

Hacking Heritage architect Marisa Brown has provided a nice review of the last five years of unconferencing here. You’ll see that the first year of the event was primarily a way to survey various folks doing cultural heritage work in and around Providence, an opportunity to informally exchange ideas and share resources. In later years, you start to see that particular projects began as conversations at unconference sessions: the 2017 Fogarty Building “obituary” and “funeral” and the Year of The City initiative in 2019 were perhaps the most visible outputs from Hacking Heritage. The “Fogarty Funeral” was a playful subversion of established sites of commemoration and discourse that critiqued the gap between a city’s cultural memory and the preservation work needed to document and acknowledge these dimensions of its built environment. Year of The City aspired to be an non-hierarchical survey of Providence’s twenty-five neighborhoods, a conceptual connective that made the range of approaches to cultural heritage and their attendant practitioners more visible and more entwined with particular regions and neighborhoods. These projects and their attendant aspirations and methodologies could not be implemented in a single day, but the space of the unconference, like the spaces provided by various THATCamp initiatives, supported their journey from speculation to reality.

On the other hand, the work described above is often initiated by established institutions and known entities in the city’s cultural sector, and we’ve wondered where and how the “unconference” framing’s legibility as an academic adjacent has shaped its audience and value. For 2020’s Hacking Heritage event, Marisa and her collaborators have focused on the Silver Lake neighborhood of Providence, a decision designed to move the event off Brown’s campus and to center conversations and work on a particular region and the interests and perspectives of some of its residents. Unconference prep has involved outreach and planning meetings with interested Silver Lake residents, in addition to the now-expected pool of local practitioners from the city. These initial conversations have involved forms of preparation, development, and staging that would perhaps rankle the unconference purist, while also retaining the blanket call for proposals and the pitching and sorting of panels that takes place at the event.

Where an unconference designed explicitly for academics might lean into spontaneity and informality as a change or even a corrective to traditional modes of conferencing and dialogue, an event that aspires to reach and resonate with other audiences must navigate other sets of expectations and forms of exchange. If you’re inviting folks to share their perspectives and spend time with you on a weekend, the potential for transactional currencies should be acknowledged and refined a bit further. I don’t think attention to such issues means that unconferences have been absorbed by the neoliberal cultural heritage industrial complex. In fact, the disavowal of the presence of hierarchies, particular forms of communication, and cloistered dimensions of unconferences seems worse. Which is to say that like most things we do, unconferencing works best when it is self-reflective and open to critique and revision.

THATCamp and other forms of digital humanities unconferencing have seemed most successful in making networks of like-minded practitioners visible to one another, in making folks feel like their work and ideas have value, in trading strategies for moving forward. These are important things! And as digital humanities practitioners think more about the public-facing dimensions of their work and opportunities for collaboration, we should think about the development of programming that builds on the strengths of the unconference model: relatively affordable, invested in models of attendance and forms of participation that do not result in the prevalence of passive “spectators” (though I think spectators should also be encouraged), cognizant of what can and can not be accomplished in a limited time span. But we also might want to exorcise the specter of the conference that haunts these kinds of spaces. There’s a lot of potential for a variety of forms of interaction, curation, pedagogy, and speculation, but creating room for successful avenues of engagement and collaboration might require a bit more preparation and outreach and strategizing before the day gets underway.

Return of The Yack

(If Dan can break out the WAAF references in his post, then I can invoke Mark Morrison.)

More seriously, one of the things I’ve loved about Dan’s ongoing work is that it has really brought back “the yack” to DH: he’s got an active microblog, a podcast, a newsletter, and I’m sure he’s designing a zine to print with Huskiana Press over at Northeastern any day now. A commitment to these sites of dialogue and communication seems very much in line with the ethos of THATCamp, in that we’re seeing thoughts in various stages of development, work in progress, recommendations that expand our lines of sight, multiple perspectives represented via interview subjects and hyperlinks. There are formal and polished elements and limitations and conventions in these particular outputs (and, in the case of the podcast, collaborative dimensions), but much less so than the traditional conference panel presentation or session remarks. And the stream of updates is much more manageable than the comparatively endless and overpopulated feed of Twitter or Facebook, still very much social media, but much less of a hellscape or a cacophony.

I remember disliking the THATCamp blogging model back in 2013, because by then I had recently created a “professional” Twitter account (I first joined Twitter in the less hyperprofessionalized days of 2007, when it was more like a WhatsApp backchannel and there weren’t any hashtags) and I had my own WordPress blog, so it felt extraneous to share writing there on what seemed like a burner account. But the centrality of blogging in the THATCamp model does serve as a reminder of how important these spaces were as counter-sites to conversations happening in other professional and institutional channels.

I am sure some nostalgia is shaping this view of blogs, but I do wonder if the legacy of THATCamp might be most visible in a reinvigoration of these kinds of spaces. It’s hard to maintain a regular and active presence in a blog, a newsletter, or a podcast, as many folks can attest (I think I started writing this post last week? It’s been a long and fractured 2020 over here). And as many folks can also attest, other forms of written labor are much more valuable and legible to the various institutions and administrators keeping the gates here in digital humanities. But when I review the key characteristics of THATCamps — informal, lightweight, collaborative, inexpensive, not-for-profit, spontaneous, timely, online — these are the sorts of online spaces of meeting and reflection I get excited about. And I think there’s a lot of potential for growth here in 2020.

This post originally appeared on Jim’s personal blog; thanks to Amanda French for offering to host it on the THATCamp Retrospective site as well. Questions, comments? Feel free to email me at james_mcgrath@brown.edu or get in touch with me on Twitter @JimMc_Grath.